I have sometimes discussed the recurring themes in my novels on this blog. For example religious oppression and abuse of power are mainstays in all my work. Children of the Folded Valley is perhaps the most obvious example.

Another key factor in my books is good versus evil. Inevitably this is born out of my Christian worldview, and since it is Easter perhaps now is a good time to reflect on this a little. For example, if I ever decide to explore the idea of good and evil being two sides of a coin, then I would prefer to think of Michael and Lucifer rather than God and Lucifer, as the afore-mentioned beings are of the same equivalent power. God by contrast is (in my worldview) far more powerful than either.

Themes of good versus evil are found in many of my favourite films and novels. Watership Down is about the price of fighting evil. The Untouchables is about refusing to compromise in the face of evil. With one key character (Snape), the Harry Potter series explores the motivations of why people stand on the side of good or evil. Then of course Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings are not only about overcoming external evil, but about overcoming the evil in oneself – or not, as the case may be.

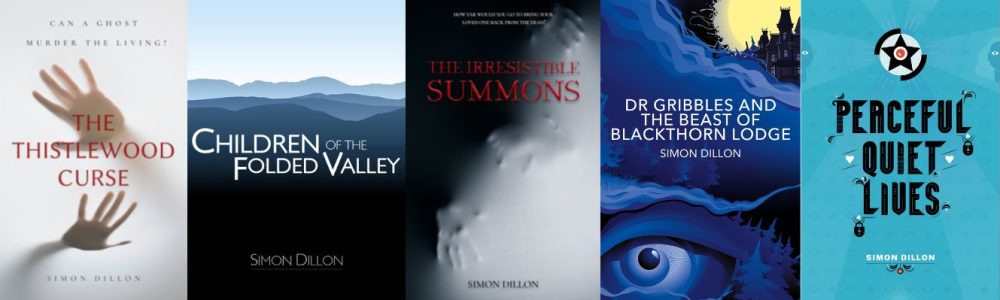

In my own work, this latter point is something I have examined certainly in certain novels. The arc from bully to hero by one key character in the second and third novels of the George Hughes trilogy is an example. The descent into religious fundamentalism by certain characters in Love vs Honour, and the Faustian descent into murder depicted in my upcoming novel The Thistlewood Curse stand in stark contrast to this.

Although I write antagonists with shades of grey, and include motivations, ultimately I do write from a worldview of good standing against evil, whatever the context. As I explained earlier this worldview is essentially a Judeo-Christian one, which I know stands at odds with writers who take a more anti-theist or moral relativist position. I must confess that whilst I admire many works written by such writers, I could never write like that myself, simply because it would not sound convincing. I can only write what I believe.

In short, in virtually all my stories, there is a clash of sorts between good and evil. I can’t see that changing any time soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.