A recent article in the Guardian reported how a library in Virginia had banned To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn because they contained racist language. News of such idiotic censorship always depresses me, and the problem is hardly a new one. Anyone with half a brain who has read those books would understand that the message of both is anything but racist. However, for some it seems the mere depiction of racism means the book must be, in itself, racist.

Schindler’s Ark chronicles unspeakable atrocities against the Jews. Does that make it anti-Semitic? Is the oppression of women promoted by the events of The Handmaid’s Tale? Does 1984 endorse totalitarian police state brutality? Is Trainspotting pro-drugs? Is The Kite Runner pro-child rape? Is The Godfather pro-organised crime? I could go on and on.

Such preposterous views have always blighted art throughout the ages. I have, over the years, vehemently disagreed with some of my fellow Christian believers, who condemn depictions of sex, violence or bad language regardless of context. For such zealots, watching or reading such things is “sinful”. I could not disagree more. The Bible itself is packed with sex and violence, not just mentioned in passing either. Several sections contain what one might say “too much information” with regards to sexual matters, and there is enough gruesome imagery to last a lifetime (who, for instance, would dare to make a film based on the final chapters of Judges – a story that begins with gang rape and dismemberment and builds to a full blown massacre). Oh, but the context is different, such zealots claim. My point entirely. Context is everything.

A book, play or film may be fiercely violent, full of profane language and ill-advised sexual activity, yet still be a moral tale. In fact, not including such material in certain contexts would make the story immoral. For example, I would argue a war film that doesn’t depict armed conflict with graphic violence is inherently dishonest and potentially dangerous. In a similar way, would that scene near the end of Babel with the completely naked Japanese girl be a tenth as dramatic if she were fully clothed? I would argue not. I watched the intensely gruesome murder near the beginning prison drama A Prophet through my fingers, but by the end of the film had to admit that had they toned the scene down it would have made the overall piece considerably less powerful.

Again, context is everything. I will concede that some people do not have the temperament for stronger material in stories, and that is perfectly fine. No one is forcing them to watch or read such material. However, what I find particularly irksome are people of a sensitive disposition who feel the need to presumptuously, patronisingly and censoriously inflict their preferences on the rest of us, for our own good.

The worst variant of such people are the religious kind, as they arrogantly profess to speak on behalf of the Almighty. For example, some of my fellow believers support their ideas about depicting sex and violence by quoting the verse from Philippians 4 verse 8 where Christians are encouraged to dwell on what is noble, lovely and true. What is “noble, lovely and true” is open to very wide debate. For example, I would argue that The Babadook is noble, lovely and true, with its cathartic and powerful themes of coming to terms with guilt and grief, but typically Christians would never endorse something as disreputable as a horror film, regardless of its message.

Conversely I would argue a film like the PG-rated Mamma Mia! is the complete opposite of noble, lovely and true. Its message is essentially it doesn’t matter who your father was, as long as your mother had loads of fun promiscuous sex. However, you don’t see me wagging my finger at my fellow believers when they choose to watch Mamma Mia! but condemn the likes of The Babadook.

But I’m getting off the point. All views are subjective (including mine). Besides, plenty of books, plays and films contain grey areas; where it is debatable whether the objectionable content depicted therein is endorsed by the context, or not. Furthermore, there are also works where appalling actions are openly and unrepentantly endorsed. Should we censor such works? Absolutely not. I say we appraise, criticise and speak out against them if we feel the need to, but should we censor them? No way.

In conclusion, I can only reiterate that whoever took that decision to remove To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from those library shelves in Virginia should be thoroughly ashamed of themselves.

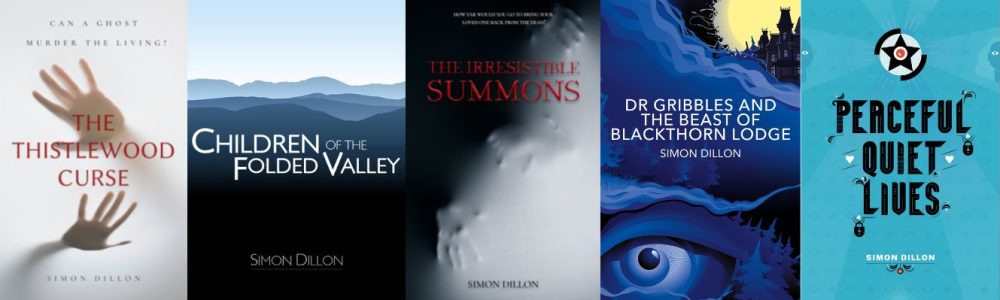

In 2016 I planned to write two novels and release two novels. I did the former but not the latter for a variety of unfortunate reasons. However, I hope to rectify that in the early months of 2017, by releasing one of the novels I intended to release last year, The Thistlewood Curse.

In 2016 I planned to write two novels and release two novels. I did the former but not the latter for a variety of unfortunate reasons. However, I hope to rectify that in the early months of 2017, by releasing one of the novels I intended to release last year, The Thistlewood Curse.

You must be logged in to post a comment.