The gothic mystery is a much-underrated genre. At their best, they are riveting tales of nail-biting suspense, heart-rending romance, and spine-tingling terror. They are stories that deal in the deepest, darkest areas of human consciousness, presenting complex protagonists with conflicting conscious and subconscious desires. They delve into the uncanny, the psychological, metaphysical, and spiritual, exploring at a primal level what most haunts us, and how love and horror can be two sides of the same coin.

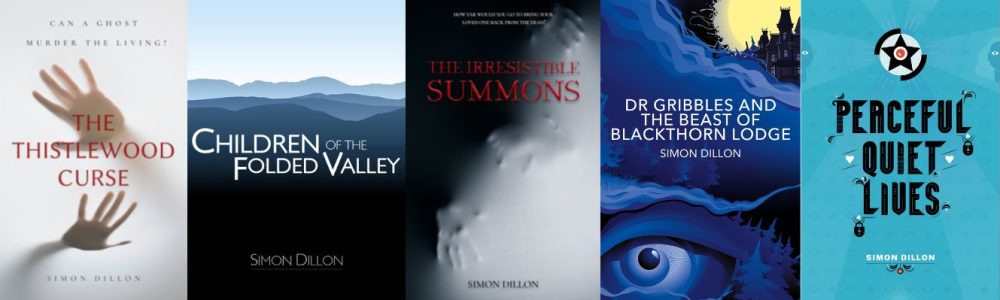

I’m a big fan of gothic mystery novels, both reading and writing them. I’ve had three traditionally published by a small indie publisher, and I’ve self-published a few others. This article is primarily for those who aspire to write in this genre, but I hope it will be inspirational and interesting for everyone. Here then are some of my insights into what makes a great gothic mystery.

Traumatised protagonists

Gothic mysteries almost always feature protagonists with significant past trauma or dark secrets. This baggage has a direct bearing on the narrative, dealing with everything from repressed sexual passions to physical or mental abuse, religious delusions, madness, and supernatural curses (which may or may not be all in the mind). Consider the traumatised Arthur Kipps in Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black, the famously nameless heroine of Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca, the similarly nameless governess in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, the passionate Cathy in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, or the eponymous Jane Eyre in Charlotte Bronte’s classic.

Most of my gothic mystery novels feature imperilled heroines. They are brave and tenacious, but often flawed by an insatiable curiosity. All have trauma and dark secrets in their pasts, that have a direct bearing on the main plot. Their character arcs are often a metaphorical descent into the underworld, entering a labyrinthine mystery culminating in cathartic confrontation of their darkest fears. Depending on the nature and choices of the protagonist, this can lead to triumphant rebirth, or an irreversible spiral into madness and worse.

The outer labyrinth

The protagonist explores the mystery, which invariably involves sinister settings. These can often be gothic locations that hide dark secrets — the mansions in Sarah Waters’s The Little Stranger and Laura Purcell’s The Silent Companions, Thornfield in Jane Eyre, Eel Marsh House in The Woman in Black — but can just as easily be modern. For instance, think of the brutalist architecture used for the Jefferson Institute in Michael Crichton’s superb 1978 film version of Robin Cook’s Coma. In one of my novels, the haunting takes place not in a spooky old house, but a modern office block in central London.

Here it is important to embrace the iconography and formula of the genre. I’ve written elsewhere about being formulaic versus being unpredictable, and with gothic mysteries, it is possible to remix ideas and still keep readers hooked and surprised. My own frequently used tropes include dark broody skies, remote haunted locations, hidden rooms, secret passages, cults or secret societies, witchcraft, ghosts, demons, and a lot of scenes involving my protagonist creeping through dark, maze-like corridors. In gothic mysteries, such imagery is as vital to the genre as hats, horses, and frontier towns in the western.

It is worth adding that when it comes to settings for gothic mysteries, a thorough, dirt-under-the-fingernails knowledge of real locations is often invaluable. I live in southwest England and have been hugely inspired by everything from rugged coastlines to sinister mansions. Having the bleak but beautiful Dartmoor on my doorstep has ensured it turns up in many of my stories, as have local histories I’ve discovered or researched in south and north Devon. One of my novels (The Thistlewood Curse) was even set on Lundy Island, in the Bristol Channel; an island with a fascinating history that informed the narrative.

The inner labyrinth

The inward labyrinth is what makes the gothic mystery even more compelling. As we journey deeper into the darkness of the central mystery, we also journey deeper inside the protagonist. In The Little Stranger, when Dr Faraday looks into the haunted house with which he is obsessed, we are also looking into him. The governess in The Turn of the Screw is another excellent example. Is she really seeing ghosts, or are the apparitions all in her head? Are they the result of religious mania and sexual repression?

The outcome of this inner journey depends on the choices made by the protagonist. Sometimes a protagonist is simply too traumatised by their experience to emerge with anything that can be termed a happy ending. The finale of The Woman in Black is a case in point. In the beginning, Kipps writes as though he has come to terms with what happened to him, but as he recounts his chilling tale, it becomes increasingly apparent that the act of doing so has simply brought all the horror back to the surface, hence this superbly terse prose at the very end:

“They asked for my story. I have told it. Enough.” — Susan Hill, The Woman in Black.

Similarly, my protagonists never emerge from their journeys unscathed, nor do they necessarily live happily ever after. Sometimes they deliberately choose evil. Such endings I refer to as DEA (Doomed Ever After), in flippant allusion to the publishing industry HEA (Happily Ever After) or HFN (Happy For Now) acronyms, frequently used in the romance genre.

Gothic horror versus gothic thriller

The descent into the inner labyrinth is a vital component of the gothic mystery and one that separates it from other kinds of thriller or horror stories. However, sometimes it is difficult to say whether a gothic mystery belongs in the horror or thriller genre. The lines can be blurred.

In the gothic genre, horror and thriller are a sliding scale, and romance can be present in both. For instance, Rebecca is a romantic gothic thriller, whereas Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a romantic gothic horror (or at least, it certainly is in Francis Ford Coppola’s film version). My novels feature examples at both extremes of the scale, with some my notoriously scare-averse mother has been happy to read, and others she wouldn’t touch with a bargepole.

The supernatural spectrum

Similarly, the presence of the supernatural in the gothic can be merely hinted at or accepted outright. The superb ghost stories of MR James deliver malevolent spectral entities at face value, though the great strength of those tales is they are never properly explained, thus leaving the reader to do the spiritual heavy lifting. The Woman in Black is another example where the reader is left in no doubt that a ghost is responsible for the torment and misery in the narrative.

At the other end of the scale, Rebecca isn’t really about a ghost at all in the metaphysical sense, though the influence of the dead character is felt on every page. In that respect, Rebecca is one of the greatest ghost stories ever written, even though it doesn’t actually feature a ghost, per se. Something like The Turn of the Screw falls in the middle of the spectrum, and again, my novels feature stories at both ends.

The terrible secret

Gothic mysteries often conceal a terrible secret. What lies hidden in the attic of Thornfield in Jane Eyre. The tragic truth behind the haunting of Eel Marsh house in The Woman in Black. The real reason Maxim De Winter is so haunted by his first wife in Rebecca. All these big mysteries involve dramatic reveals in their respective narratives.

Rug-pulling twists are a key part of the genre, and they are also present in my novels. Here I want to stress something that goes against advice often given to novelists. Don’t necessarily dial down melodrama in the big reveals. It is all about context, and sometimes the blunt instrument of melodrama is extremely effective when properly earned. Ask yourself honestly: Would Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre benefit from being less melodramatic?

Conclusion: How to make it personal

Often dismissed as overblown, the gothic mystery is in fact a tremendous canvas for exploring personal stories through metaphor and allegory. The best gothic fiction uses supernatural elements such as curses, ghosts, and demons to cathartically explore genuine psychological trauma. Regardless of how ambiguous or otherwise these elements might be in any given narrative, they are important symbols.

Recurrent themes of my fiction — particularly oppressive religious trauma and abuse of power — finds a natural home in the gothic mystery genre. However, I would advise against consciously inserting these with any kind of preachy agenda. It is better to simply tell a good story with these themes, rather than use your protagonist as a social or political mouthpiece. Your views will be inherent in the material in any case.

(NOTE: This article is a revised version of a piece that originally appeared on Medium.)