Stephen King famously once said there were three levels on which a horror story could work. The highest level is to horrify, the second highest to terrify and the third to repulse. He also said he wasn’t too proud to stoop to the third level, if it was the only way he could make a story work.

King’s definition has been in the back of my head throughout my own writing of horror stories (including in my upcoming novel The Thistlewood Curse). Specifically, I have thought to define further what King meant, with examples from book and film, so as to apply this to my own work in the hope that I might achieve the highest of the levels to which he (and I) aspire in writing horror.

To horrify one must tap into the deepest and most primal of fears in, a new, interesting and effective way. The Woman in Black does this well, because it explores parental fears about the death of children. Frankenstein taps into worries about morally unchecked advances in science. Dracula deals with dark and dangerous repressed sexuality and so on.

In film, The Exorcist is another good example as it also takes the theme of something terrible happening to a child, and with that theme (demonic possession) it explores all kinds of fears both directly related to the story (ie the actual literal possession) and metaphorical (subconscious fears about puberty, emergent sexuality and so forth). More recently, The Babadook delves into themes of guilt and grief in a profound and genuinely horrifying way.

As a brief aside, I would also argue that at this highest of levels, horror is ultimately about catharsis. People who do not care for the genre often comment to the effect of “Why would you put yourself through that?” to which I would reply, “Why would you put yourself through a comedy? Or a weepie?” Such stories are simply the flip side of the same coin. No-one would actually want to go through the events of a farcical comedy or an overwrought weepie any more than they would a horror story, but people enjoy them because they provide emotional release – a catharsis. In my experience, people who have been through dark events in their lives don’t avoid dark stories. By stepping into the horror protagonist’s shoes, we relate, we identify, we find meaning, and above all it can help us come to terms with our own demons.

The difference between horrifying an audience and merely terrifying them is to me a question of mechanics triumphing over the ability to relate in a meaningful way. In the case of a slasher story (Halloween for instance) there is no deep connection the audience or reader feels to those foolish teenagers who have unwisely ignored advice to stay away from the woods, or from the haunted house, or wherever else the bloodthirsty villain might lurk. To that end, such a story can expertly manipulate a reader or viewer, but whilst the result can prove gripping, it will often fail to resonate at a deeper level.

Finally, there is the option to repulse or gross-out with high levels of gore. Obviously such techniques speak for themselves. However, horror stories at this level can sometimes elevate themselves by combining gruesome bloodletting with other techniques. For example, Dawn of the Dead is a classic zombie movie not just because of the buckets of gore but because of the savage satirical undercurrent.

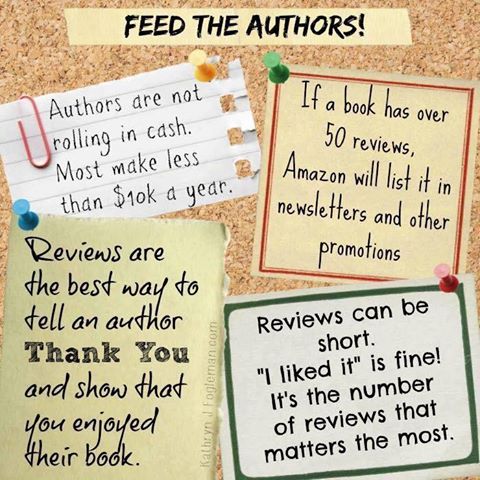

With all this in mind, I am intrigued to see what readers make of The Thistlewood Curse. I would prefer to brand it as a supernatural thriller (as I have already mentioned in previous posts) but there are unquestionably horror elements which I hope will tap into universally relatable fears in a new and interesting way. In short, by the end of the novel, I hope to horrify the reader.